In Light of Moore's "proof of an external world", try to think at these questions:

- Is commonsense knowledge unrevisable?

- How does Moore know that he has hands?

- Is it relevant whether Moore can prove that he knows that he has two hands?

- From the premises: “Here is one hand”, and "Here is another," would you be justified to conclude that an external world exists?

- If you do know you have hands then do you know there are external things? Or, if you don’t know there are external things then do you know you have hands?

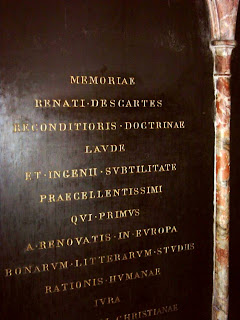

- Should Descartes be satisfied with Moore's proof?

- What is the logical form of Moore’s argument? What is a proof according to Moore?

- Do you know anything better than you have hands?

- Can you know that you have hands without already knowing that there is an external world?

- Do we have more or less reason to doubt that we know there’s an external world?

- What’s the strongest skeptical argument?

- What is the best way to respond to the problem of radical scepticism?